Dr. Elizabeth Thill has reiterated time and again to skeptics in her field that virtual reality has serious pedagogical applications. It's not just a fun way to get students interested; it is in fact integral to her curriculum. Thill uses VR in her courses on The Art and Archaeology of Rome, Myth and Reality in Classical Art, and Sex and Gender in the Ancient World, where she is able to demonstrate architectural and sculptural details of ancient artifacts in a way that is so effective, it's been game changing to her teaching.

Elizabeth Thill

Director, Classical Studies Program, IUPUI

Assistant Professor of Classical Studies in World Languages and Cultures, IUPUI

Jeannette Lehr, from UITS Student Outreach, met (in VR, of course) with Professor Elizabeth Thill and University Library's Jenny Johnson and Ryan Knapp to discuss how teaching with VR is much more than a neat trick.

About a year ago Dr. Thill met Jenny Johnson and Ryan Knapp while working on a project that involved 3D scans of ancient sculptures. Jenny Johnson is the head of digitization services for University Library and provides access to and preserves cultural heritage objects via 3D scanning. Thill was impressed with the beauty and quality of 3D scans of ancient objects, but she was not sure how they could be useful.

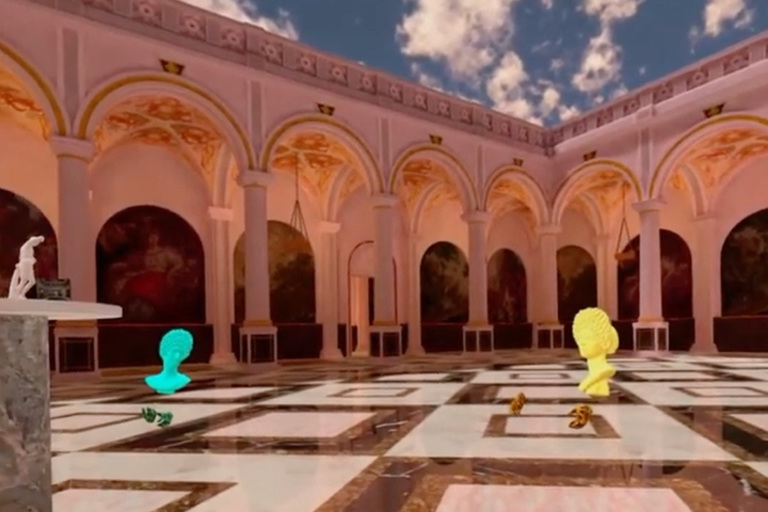

Then Ryan Knapp, technology services manager at University Library, showed Thill what the scans looked like in a high-quality VR headset. The ability to (virtually) move around and touch the artifacts impressed Thill. She was hooked, and she started using VR to teach her students about ancient artifacts. And so the journey began in fall 2019: Knapp placing the scans in VR and developing entire VR experiences, including ancient architectural buildings and environments in which to house the sculptures; Jenny facilitating the whole process; and Thill curating it all for her students.

However, with the move online in spring 2020, Thill went back to using PowerPoint. It was then that she was able to see the stark difference between what had once been her preferred teaching tool, PowerPoint, and what has emerged as the best way to convey information about the ancient world: virtual reality. After a semester of settling for 2D presentations, Thill went back to teaching with VR for the fall semester of 2020. Even displaying the VR experience to her students in remote Zoom lectures far surpasses the old model.

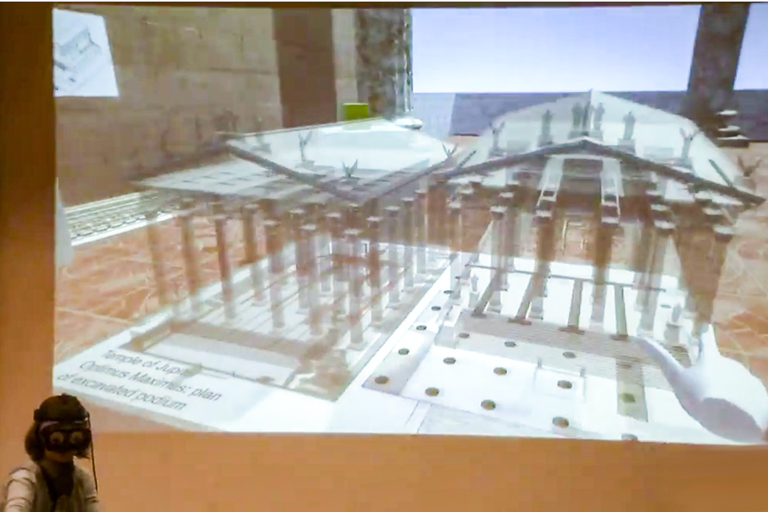

"I thought students would be annoyed with glitches, but they mostly think it's funny," said Thill. They all laughed when she got trapped under the Athenian Acropolis. "I think they really enjoy the sense of cutting-edge technology."

A lot of instructors think that in order to use VR in their classes, every student would have to have a VR headset. But Thill suggests starting with demonstrating VR by having one quality $300 headset and projecting the display onto a screen for the class to see. Students don't have to put on the headset to have a quality learning experience. In addition, many students are visual learners and being able to see artifacts from different angles in VR, or to see a professor like Thill walk around a space, gives them a deeper understanding.

With VR, Thill can spend her valuable time preparing more substantive content for her lectures. Instead of being able to talk about only a couple of sculptures using 2D slides and lots of time describing them, she is able to pick up 16 different sculptures and raise them in the air for students to see from different angles. They get to see it all in-depth and much more efficiently in VR. It opens up so much more time for her to talk about the meaning behind the qualities of the architecture and artifacts—what it means that the building was structured in certain ways, and that's really the more important part.

Knapp and Johnson believe that this kind of opportunity will be expanded to more students when educators and administrators get the chance to try out high-quality headsets for themselves. Knapp and Johnson believe that when you see it for yourself, you can't ignore the potential. Thill feels the same way about buy-in for professionals in her field. "In classical studies, we're used to putting together tiny paper models of the Forum of Trajan and seeing which one looks stupider. Whereas Ryan can build me an entire Forum of Trajan in VR that I can walk through and test hypotheses," said Thill. Only time will tell when and if VR takes off in higher education, but if you ask Thill, now is a great time to start.

Favorites and the future of VR

When asked about their favorite things about VR and their next steps in the medium, each of our VR experts had this to say:

Jenny Johnson

Johnson said that seeing the student reactions to VR and inspiring them to pursue this technology is what impressed her most about this endeavor. "We may be changing future careers," she said.

For Johnson, an ideal future for this line of work is one where VR and 3D digitization are core services of academic libraries. She sees a long-lasting future for this kind of work and thinks it has the potential to be game-changing for many university library systems.

Ryan Knapp

For Knapp, knowing that there are so many things to come that we haven't seen yet is the most exciting thing about VR. "In VR, you aren't bound by the limitations of the physical world," he said. People who wouldn't normally have the opportunity to go to Rome, or even Mars, will have the opportunity to do so in a realistic way.

Knapp's next steps will be creating multi-user virtual learning spaces where students and instructors can interact together in a simulated classroom environment. And then, taking it outside the classroom is after that. Knapp's ultimate goal is to build a realistic and immersive recreation of Ancient Rome so students can travel the streets, view the architecture, and learn what it was like to walk the streets of Rome.

Dr. Thill

VR is a democratized medium, and that is what Thill loves the most about VR. VR is a way to bring things and experiences to people who couldn't otherwise afford to experience them. Like other new technologies in the past, VR opens up options to more people. Thill really believes that VR is not just nifty; it's game changing. "We're talking about hard core research, hard core pedagogical advantages," Thill said. "You can do things in VR that you cannot do in real life."

For Thill, the next step will be a debate held in VR, in the Parthenon. She says students will be joining the virtual space this time. All of the technical details haven't been worked out yet, but Thill is excited to get students into VR to interact with the ancient world in an even more immersive way.

What should instructors do if they’re interested in exploring VR?

Thill cautions instructors who are new to VR not to try to create the more in-depth experiences, similar to what she's been doing, on their own. If you want to create customized experiences, you need someone like Johnson and Knapp to help you with the technology development aspect. Thill is thankful that IUPUI has staff in the position to do this kind of work with VR. Thill believes this work is worthy of professional support and she hopes all campuses will have VR developers on staff eventually. Knapp says that even if you don't teach from the IUPUI campus, "I would encourage instructors to talk with us. We're happy to work with them on finding different possible applications." They said once instructors come up with a need to ask for help.

Thill recommends going at VR with very specific pedagogical goals. Adjust your expectations. Especially in the beginning, you won't be able to have everything you want in VR, but you can do a lot.

Read more about Thill's work in VR in a piece written for IUPUI's The Campus Citizen, or experience a VR tour with Thill below.

Credits and contact

This team's research has received very generous support from the IUPUI Arts and Humanities Institute and is now part of their Incubator Project with Dr. Jason Kelly. The student participation has been funded by the UL + CDS and the IUPUI Center for Research and Learning, now part of the IUPUI Division of Undergraduate Education. Dr. Thill, Ryan Knapp, and Jenny Johnson have generously offered to share their contact information with interested instructors. Feel free to contact them with questions:

Dr. Elizabeth Thill, Assistant Professor and Program Director of Classical Studies at IUPUI,

Ryan Knapp, Technology Services Manager at IUPUI’s University Library,

Jenny Johnson, Head of Digitization Services at IUPUI’s University Library,

Description of the video: